It’s well-known that Roxbury was one of the first ever “streetcar suburbs,” but until I dove into the term I didn’t have a full sense of what that meant. Roxbury did, in fact, flourish after the first streetcars but there is much more to the story.

A 1930s streetcar at Guild Row on the same route once run by horse streetcars owned by the Highland Street Railway Company.

For the first couple of hundred years of Roxbury’s existence, the only way to get around for most inhabitants was to walk unless you were wealthy enough to own a horse. In 1768, a census showed only 22 carriages in the entire city of Boston, and by 1798 there were only 145. Roxbury being much smaller, there were probably many fewer carriages. So most of the time, the poor walked and the rich rode horses. And since Roxbury didn’t get its first paved street until 1824, when Roxbury Street was paved and brick sidewalks installed, going anywhere usually involved a lot of mud and very wet feet.

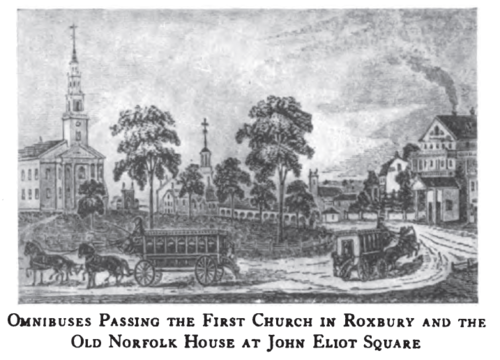

Because of that, the community was small and dense. Roxbury Street around Eliot Square (then known as meeting house hill because of the first church) was the major commercial district, with another large cluster of commercial buildings eventually growing up around the crossroads at Dudley Square. A trip to downtown Boston would have involved an hour long walk or a slightly shorter ride on a horse, so you wouldn’t have been likely to venture into town very often. If you had frequent business in Boston, you would probably move closer in.

But by the mid-1820s, commerce between Boston and the surrounding cities and towns started to grow. In 1826 or 1827, stage coach services connecting Boston with Roxbury, Charlestown, and East Cambridge appeared. The Roxbury line terminated at the original Norfolk House, which was built in 1825. These services were small, enclosed horse cars with benches facing forwards, like those pictured in most westerns. This was not an optimal layout for passengers to get in and out frequently, they couldn’t carry many passengers, and they ran only hourly. But they were a start.

By 1833, a man named Horace King, who had been employed as a waiter and general utility man at the Norfolk House for several years and had been saving his pennies, saw an opportunity to improve service. He bought two vehicles, one of which was named the “Governor Brooks,” laid them out with the seats running along the sides facing each other and a door at each end of the car to make it easy to get in and out, and started the first omnibus service in Boston, from Norfolk House to the ferry at the foot of Hanover Street. The round trip was 2 and 1/2 hours and the fare was 12 1/2 cents.

These first omnibuses were drawn by 4 horses with room for 24 passengers, 18 inside and 6 outside. He experimented with various sizes of coach, from small 2-horse, 12-passenger affairs to massive 6-horse jobs that carried over 40 passengers, over the years. There’s a marvelous children’s book called “Marco and Paul’s Voyages & Travels: Boston" that tells the story of two young men traveling from New York to Boston. In it, young Marco sees his first Roxbury omnibus:

Paul goes on to explain that the larger omnibuses were something of an express route from Roxbury to downtown. The smaller omnibuses were used on local routes, since the frequent stops and starts on a local route with a larger, heavier vehicle tired the horses out too quickly.

Within a few years King had control of almost all of the omnibus lines into the city and had over 250 horses and 150 men working for him. He eventually bought and enlarged the Norfolk House and became incredibly successful, only to lose everything in the financial panic of 1856. He moved home to Rutland and spent his last 40 years there in relative penury, eventually dying at the ripe old age of 96 in 1903. To read more of his story, click on this link.

The next mode of transit to connect Roxbury to Boston was the steam railroad. The Boston and Providence Railroad had started construction in 1832, and the spur to Dedham opened in 1834. The Dedham spur followed the Stony Brook valley through Roxbury and had a stop at Roxbury Crossing. But the train was less convenient and more expensive than the omnibus so it never really competed on the Roxbury Crossing stop, doing more to serve passengers coming in from farther away.

A view of the old Roxbury Crossing Station, with some of the first electric streetcars, just after the turn of the last century.

Between the omnibus service to various points in Roxbury and the train service, Roxbury’s population finally started growing. In 1800, the town had a population of about 2700. Thirty years later, after the coach service had started but before the omnibus and train were in operation, it was over 5200. In the next 10 years, it grew to just over 9,000. By 1850 it had doubled to over 18,000, with the vast majority of people riding omnibuses when they wanted to visit Boston or travel to Dorchester, Cambridge, West Roxbury, JP, or other suburbs.

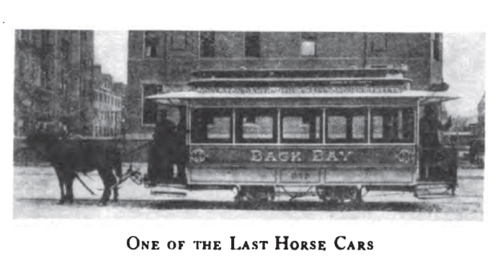

With the rapid growth in metro Boston, it was only a matter of time until a more efficient method of moving people from point to point became a necessity. In 1856 that method finally arrived, in the form of the street railway system that had been pioneered in New York starting in 1852. The first street railway system in Boston ran to Cambridge on March 26, 1856, followed in September by the Metropolitan railway company’s original line from Guild Row in Dudley Square to Scollay Square.

The street railway operators were private, for-profit operations that received charters from the state legislature to build their tracks on city streets. The railway cars were drawn by horses and quickly settled into 4 major companies that each had a monopoly over its service territory, with the Metropolitan railway having the largest territory, serving East Boston, the Back Bay, Roxbury, Dorchester, Milton, JP, and Brookline.

The first street railways weren’t necessarily popular with everyone. Because they paved the area between the tracks, which was the only paved area in the street, people preferred to walk between the tracks. Of course, this meant that they constantly had to move when the trains came, and for a brief time there was the complaint of “too many trains” from the pedestrian population. In Cambridge, the railway company’s opponents tore the tracks out of the street in the middle of the night on several occasions. But before long the horse-drawn railroads gained acceptance, although the omnibus didn’t completely fade away for another 50 years.

The consolidation of the competition into 4 monopolistic lines eventually led to a decline in service, and by 1872 there were loud cries for more competition. Among those demanding better service was our neighborhood’s own William Lloyd Garrison, who used his well-practiced sense of outrage. In a letter from February of 1872 he bemoaned the situation to James Ritchie, a notable Roxbury resident and a man who was at the time one of the principal assessors for the city of Boston: “[The Metropolitan Railway Company] takes undue advantage of our Highland residents by inexcusably compelling them to be packed in those cars, frequently three times, and usually twice, beyond the number of seats provided; outraging all sense of propriety, at times bordering on indecency, in the enforced crowding together in a standing position of virtuous and refined ladies with coarse and vulgar men,—an exposure most trying not only to female delicacy, but highly favorable to the operations of pickpockets of both sexes.”

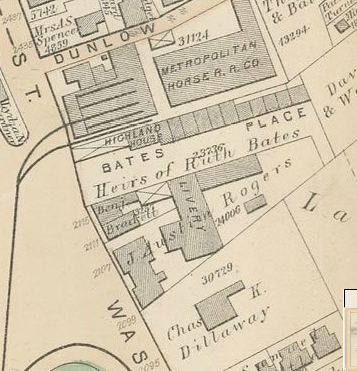

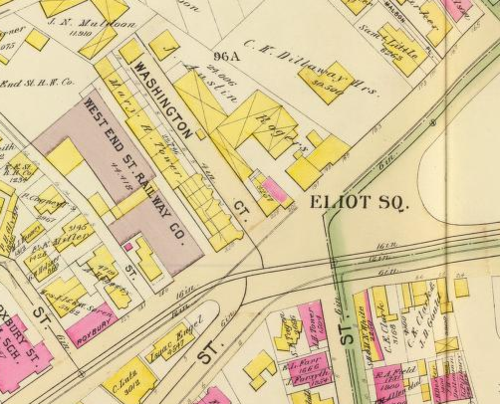

The 1873 map shows the Metropolitan horse barn at Eliot Square

Garrison and other residents were successful in getting more competition on the horse railways, and beginning in 1872 the Highland Railway company operated a service on the same lines that was widely regarded to be superior to the Metropolitan. Of course, the arrangement meant that the Highland and other competing lines were using some of the tracks laid by the original railway companies, which were bitterly upset by this turn of events. There were notable battles between the various companies, especially at the more popular spots where operators would jostle to become the first car in line, and if they lost out they would run the car as slowly as possible to try to become the first car at the next big stop.

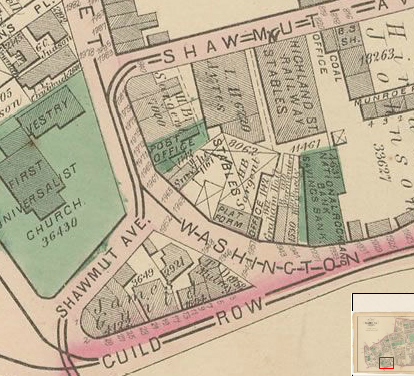

The same 1873 map shows the Highland Street Railway barn in Dudley behind Guild Row. The Highland’s tracks ran up Shawmut, the Metropolitan’s up Washington.

In 1887, a businessman named Henry Whitney bought a huge tract of land in Brookline and commissioned Frederick Law Olmsted to lay out Beacon Street as a grand boulevard. He laid railway tracks down this new street and formed his own railway company, the West End Street Railway Company, to shuttle people back and forth to his new subdivision. The venture was a huge success, but the state of the other railway companies was so dismal that Whitney decided to take ownership of them so that his customers could get to their new homes more efficiently. Amazingly, he was able to buy almost all of the old companies within the course of a year, and by the end of 1887 the West End Railway had 10,000 horses and all of the major street railways in Boston under its control.

The West End Railway horse barn in Eliot Square, at the same location as the Metropolitan barn shown above in the 1873 map. The company had a larger barn on the site of the current MBTA bus yard at Bartlett Street and another one roughly on the site of today’s Jackson Square T stop.

Before long, the West End railway was working on plans to electrify the system and remove the need for thousands of horses to haul passengers. Within 20 years, the era of horse-drawn transit in Boston was over.

If you’re interested in finding out more about the rapid changes in rapid transit, there are plenty of good sources that detail Roxbury’s role:

From Coach and Omnibus to Electric Car

Bacon’s Dictionary of Boston: Street Railroads

The Street Railway System of Metropolitan Boston

Moving the Masses: Urban Public Transit in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia 1880-1912

William Lloyd Garrison’s letter to James Ritchie

Streetcar Suburbs: The Process of Growth in Boston 1870-1900