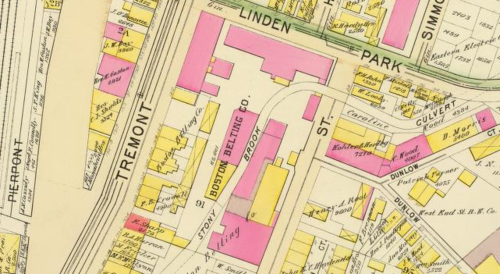

The Stony Brook provided water for more than just breweries. There were dozens of other industries located along its meandering path. One of the first most interesting was the Boston Belting Company. The company was one of our earlier industries, chartered in 1828 along the Stony Brook, in approximately the present-day spot of the Reggie Lewis Center and the Islamic Society mosque.

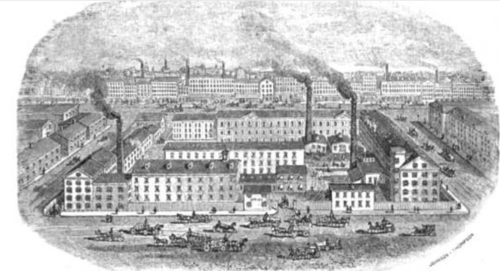

The Boston Belting Co in 1895. The site was located about where the Reggie Lewis Center and the intersection of Malcolm X and Columbus Avenue now are.

Just a few years earlier, sometime about 1820, a sea captain had brought back a pair of rubber shoes from his travels to Ecuador. Boston being a cold, wet place much of the year, people immediately seized on the utility of rubber boots and shoes. Since rubber could be had for next to nothing and the shoes could be sold for $2 a pair or more, there was something of a speculative boom in the rubber shoe market, soon followed by other rubber products. The Roxbury India Rubber Company was born, led by Edwin Marcus Chaffee, and as much as $2 million in stock was sold based on the promise of the sale of thousands of pairs of shoes and other rubber goods.

An 1880s-era ad from the collection of the Davistown Museum.

In the early 1830s, a bankrupt Philadelphia inventor named Charles Goodyear passed by the Roxbury India Rubber Company’s storefront in Manhattan and bought an inflatable rubber life preserver out of curiosity. Being an innovative sort, he quickly devised an improvement for the flimsy inflation tube and offered to sell his improvement to the Roxbury Rubber folks. Unfortunately, the proprietor told him a tale of woe: rubber, while a fine product in Brazil, was lousy for the Northeast US. It was rock-hard in the winter, and turned into a gummy, stinking mess by the time July heat came around. So many outraged customers had returned products that the company’s directors had been forced to bury the stinking mess of rejects in a pit in the middle of the night.

Goodyear, dismayed, returned to Philadelphia and was promptly tossed in jail for nonpayment of debts. He asked his wife, who must really have seen something in him to stick with him through all of his adventures, to bring him some rubber and a rolling pin and whiled away his time behind bars experimenting with the substance. Eventually he was released and continued his experiments through a series of failures and poverty in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston.

Goodyear ended up as something of a charity case in Woburn, where in 1839, more than 5 years after his fateful purchase of the life preserver, he stumbled upon “vulcanization,” the combination of heat and sulfur that would stabilize rubber and revolutionize life as we know it. Life didn’t get much better for Mr. Goodyear after that, though, as he suffered health effects from the noxious chemicals he experimented with, made pathetically bad business decisions, and found himself embroiled as the plaintiff in literally dozens of patent lawsuits at home and in the UK. His whole sad story is recounted in great detail at a number of places around the web. If you want more info start with the official Goodyear company history, then moving on to “Jacksonian Memories #55.”

It’s not exactly clear what happened during those mid-1830s years in Boston, but he certainly worked with E.M. Chaffee and the proprietors of the nearby Boston Belting Company. In fact, after he finally patented his vulcanization process in 1844, the Boston Belting Company briefly changed its name to the Goodyear Rubber Company before changing it back a couple of years later. Chaffee was forced to sell a $30,000 rubber machine for just a few hundred dollars in the early 1840s, before Goodyear had perfected his process.

Chaffee, Goodyear, and Henry Edwards, the apparent proprietor of the Boston Belting Company, continued to cross paths routinely, with things culminating in an 1850s patent case featuring Chaffee as the plaintiff and the Belting Company as the defendant, which Chaffee eventually won on appeal. The patent in question had originally been given to Goodyear, who had licensed it to Edwards.

Unfortunately for poor Charles Goodyear, he continued to bounce in and out of poverty - and debtor’s prisons - until his death at age 61 in 1860. Fortunately for his long-suffering family, some of his patent royalties eventually panned out after his death and they were able to live in relative ease. The company that bears his name has nothing to do with him. It was started in 1898 and named in his honor. Chaffee’s fate is less well-documented.

The Boston Belting Company, thanks to the pioneering work of Goodyear, went on to thrive for many more decades making a huge variety of belts, hoses, and other rubber goods. Here’s an ad from the February 9, 1863, edition of the Sacramento Daily Union:

And the firm’s entry in the 1889 “Illustrated Boston" gushes about the firm’s pre-eminence in the global rubber trade and the 2-acre site with 400 employees, as shown here from its entrance on Linden Park Street (a street which has been obliterated by urban renewal along with the factory). It’s hard to believe that our neighborhood was once home to the world’s largest industrial rubber manufacturing operation, or that this operation spawned a massive rubber industry in Massachusetts, but it did.

The firm had a long and colorful history, including a near-disaster due to poor management (PDF) from one John Tappan in 1878. The company was also involved in a long-running lawsuit against the city for altering the Stony Brook, which it had used since 1828 as a source of water and power for its operations. The alterations to the brook took place in 1874, but the lawsuit dragged on until 1903. It also survived some intense competition, including the 1892 formation of the Rubber Trust by the US Rubber Company. The firm was still going strong in 1916, when it was reported to have assets of $2 million and pay 8% dividends, and this 1923 advertisement in Forbes celebrates its 95th year. After that, the trail goes cold.

If you have any more info about the final chapter of the Boston Belting Company, please let me know.